The Ransomware Economy is in the Spotlight and Hackers are Feeling the Heat

– Stel Valavanis, CEO of onShore Security

Ransomware is hot. In 2020, it grew by 336%, with more than 370 million dollars in cryptocurrency paid to hackers and the “vendors” that support them. Ransomware is driving the cybercrime economy and helping it to grow, but it might also be its biggest problem.

From Solitary Attackers to Enterprise Operations

Ransomware has historically had the benefit of a reputation as a cottage industry, with the image of an attacker still being that of a lone black hat in a dark basement, but in reality, cybercriminals have the capability of large, legal businesses, with access to a whole ecosystem of supporting vendors, franchise opportunity, and services specialized to allow what is being referred to as “ransomware as a service”. This empowers the criminals to target bigger organizations for bigger payouts and, while individuals may feel safer these days, it is actually even more likely to be hit by ransomware, and more likely to be affected when others get hit. The collateral damage, such as gas shortages, increases with the size (and importance) of the targets.

As ransomware gangs set their sights higher, attacking large organizations instead of individuals, their targets have begun to include assets that are under government protection and oversight. Government agencies have a vested interest in investigating and prosecuting such attacks. Ransomware is hot but, in fact, may be too hot.

Enormous Capacity to Wreck Havoc and Gain Unwanted Attention

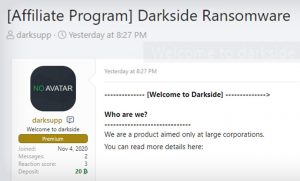

The recent attack on the Colonial Pipeline by the group known as DarkSide, for example, had a major impact on US infrastructure, specifically our energy and oil supply, and opened many eyes to the real danger that ransomware attacks pose. The scale of the attack made it reasonable to categorize the attack as terrorist activity and attract the additional scrutiny and interest that the terrorism label carries. Criminal hackers, who assumed the safety of obscurity, feared the level of attention and response an attack such as this might bring on the entire cybercrime ecosystem. This event itself precipitated calls for “moderation” amongst cyberattacks and a quick ban on discussion of ransomware on the forums where cybercriminals meet, discuss tactics and targets, and trade illegal tools and stolen information, in an attempt to avoid the attention that ransomware attacks have started to garner.

Because suppliers represent exposure, many criminal gangs are moving to end their outsourcing and do everything privately, “in-house”. The current “affiliate” model, by which criminals franchise their operation, offering their tools for a cut of the profit, may soon go away as it poses too much risk as legal and governmental agencies develop their understanding of the ecosystem and adopt more direct tactics to shut the many different parts of the ransomware machine down.

Evolving Ever More Dangerously Underground

Cybercriminals survive by being willing to adapt and it’s policy they’re responding to. The ransomware industry has grown quickly because it has had the room to do so, making moves that would typically be too risky for a criminal enterprise. Ransomware has become big business, with many of the same organizational risks that legitimate businesses face as they grow their operation. As ransomware operations change, we must not presume their death. Even DarkSide survived their moment in the spotlight, turning to a classic public relations maneuver for a company faced with scandal: they rebranded. The new “brand”, Black Matter, is following the new rules of engagement that President Biden tried to set at recent meetings with Russian leader Vladimir Putin. Black Matter is reported to be avoiding targets that are part of the U.S. infrastructure, and so it seems some of Biden’s cyberdiplomacy is working.

A scarier shift is that some of these entities are testing out new technology as they change their focus. While criminal hacking gangs have historically been relatively unsophisticated in their technique, using lightweight, off-the-shelf (literally purchased) programs, the Hafnium attack and others display a potential for much greater attack capability, elevating the threat of many of these groups beyond petty cybercrime to cyberwarfare and cyberterrorism.

Putting Pressure on Nation State Support

Up to now, the majority of criminal hackers attacking the United States have done so from the safety of our adversaries, within Russia, China, and other countries, often unobscured, sometimes working in official capacities as government agents or members of the military, other times with less explicit support. The operations of these cybercriminal cells is covered up enough to offer their host country plausible deniability for anything that comes of out of the shop, and the hackers have historically been left alone or even protected by their home government, as long as they follow two simple rules: Don’t attack at home (often leaving the US as the main target) and don’t make too much noise.

As the US starts to do some of the more basic footwork to stop ransomware (as seen in the effort to recover the ransom from the Colonial Pipeline attack), there will either have to be a greater effort on host countries to police the cybercrime in their jurisdiction, or they will have to do a better job of covering up their connections to the criminals. The cybercriminal world leaves much of their work visible to the public, relying on the lack of scrutiny to operate in the open. As the US government turns its sights on cybercrime, the preparation and effort put into tracking threats, stopping attacks, and improving our security posture puts pressure on cybercriminal gangs, and the state actors behind them, to stop attacks on the US government and people. We shall see if what doesn’t kill them makes them stronger.

Photo credit: KELA